Table of Contents

I’ve been watching videos some people consider to be 1st Amendment Audits, for at least 3 to 5 years I would say I’m an expert when it comes to defining a first amendment audit. I have seen pretty much every single channel and I recognize each of their style. I think they are important and first amendment audits are the main reason I started this website.

Keep that in the back of your mind as the bias I have towards First amendment audits and other types of public photography audits, I will try to define what a First Amendment Audit is. You should also read the about page and the resources pages for more information about this site if you’re going to make a judgment on this content.

I try to be as neutral as possible since I just want to answer questions about 1st amendment audits. You can also see examples of 1st Amendment Audits documented here on this site just by doing a search or clicking here.

When I tell people I have this site or that I watch these videos, they ask me so what are first amendment audits? It’s hard to explain, but I’ll do it next.

What is a First Amendment Audit?

This is my 1st amendment audit definition:

A first amendment audit is a review of the processes, procedures, policies and legislation as they relate to the act of exercising the natural rights protected by the 1st amendment of the US constitution.

A first amendment audit is a review of the processes, procedures, policies and legislation as they relate to the act of exercising the natural rights protected by the 1st amendment of the US constitution.

A first amendment audit is usually conducted by a member of the public (the people) and it’s conducted on a government-related facility or government regulated event. It’s becoming more of a norm to extend 1st amendmend audits to non governmental entities as well. This post explores the ins and outs of First Amendment Audits.

In a different way of saying it, a 1st amendment audit is a review of the procedures and policies in place that may interfere with a person’s natural right to freedom of speech, freedom of the press and freedom to gather and/or demand reprieve from the government.

On social media, you’ll find it under hashtags: #1aaudit #1stamendmentaudit

First, let’s go over out what exactly is the 1st amendment.

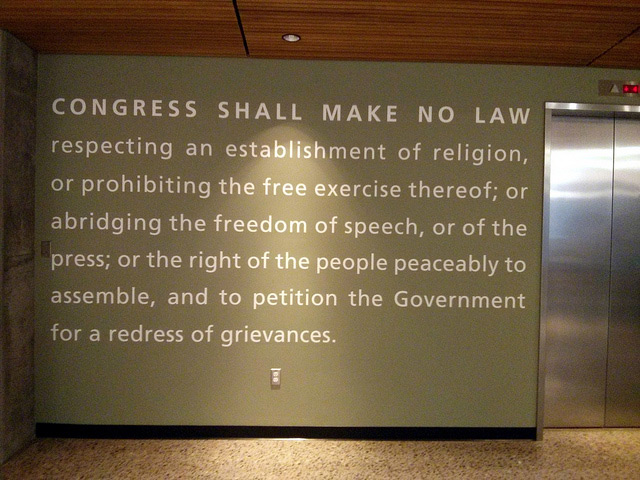

Let’s look at the first amendment of the United States Constitution, arguably the strongest foundational pillar for the amazing society we have today and that we enjoy here in the USA. It is the 1st amendment in order and also the most important for all the other ones rest on the freedoms this one guarantees.

First Amendment says:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

So if we break it down to the 5 freedoms protected by the 1st amendment, each one with the exception of freedom of religion directly relates to first amendment audits. Let’s take a look:

Freedom of Speech.

Auditors have the right to express their opinions (freedom of speech). This comes into play many times when an auditor is narrating or speaking while auditing.

Freedom of the Press is one of the 5 freedoms guaranteed under the 1st amendment.

Freedom of the Press is one of the 5 freedoms guaranteed under the 1st amendment.

photo: Press Freedom Scrabble photo CC by Jeff Djevdet[/caption]

Freedom of the press.

The freedom of the press is extended to every single individual under the jurisdiction of the US Constitution.

That means that you and I are members of the press if we so choose to.

At any given point, you can record a public incident or anything you can see from a vantage point you are legally allowed to be in. You can do this just because you can and there is no law against it. But you are also protected to do this because you may be gathering content to distribute it as a press related document.

You do NOT have to have media credentials to be a member of the press.

You only need media credentials for privately held press conferences where you are subject to their access requirements.

The right of the people to assemble.

In many cases, you will see that the auditors conduct first amendment audits in groups of 2 or more. This act in and of itself is protected by the fact that we have the right to assemble with others for whatever purpose we want (almost — but virtually for every purpose that relates to first amendment audits).

Petition of the government for a redress of grievances

This is a big one during many first amendment audits. In many cases, an audit is related to public criminal or civil cases, complaints or applications for permits and other government-related activities.

During the process of whatever activity it may be, the citizen may want to document it and by law, he is allowed to do it and that includes using a video recorder to do so.

photo “First Amendment Mural” by Cory Doctorow, used under CC.

There are some cases where the recording of activity is restricted lawfully but these are very rare such as the inside of a courtroom, by judge’s orders, or in restricted areas within a public building where you agree to said terms –and the validity of this is often brought into question.

The relationship between 1st Amendment audits to the 1st Amendment is clear and direct.

So as you can see, four out of the five freedoms guaranteed by the 1st amendment apply to many 1st amendment audits.

When a cop, law enforcement unit, civilian, or government employee says something to the effect that “recording a government facility” isn’t part of the first amendment, then they just may not be familiar with the entire first amendment.

I find that most people only remember the two big elements of the first amendment, freedom of speech and freedom of religion; often they forget the freedom to assemble, freedom of the press and the freedom to basically complain against the government.

But first amendment audits are bigger than just the first amendment.

In many cases, an incident that started as a First Amendment audit may turn into a 2nd amendment audit, 4th amendment audit, 5th amendment audit and a few more. In other cases, a 2nd amendment audit could become a 1st amendment audit.

For example, if a 2nd amendment auditor is walking down the street carrying a firearm legally exercising his or her 2nd amendment rights and is also recording the activity with a camera or multiple cameras this can turn into a 1st amendment audit in a second.

If a law enforcement agent shows up and demands that the camera be turned off or put away or blocks it deliberately, that becomes a 1st amendment rights violation. And it can easily be considered a 1st amendment audit because the ability to record (freedom of speech or press) is being put in jeopardy.

In essence, that person’s 1st amendment rights are being violated.

From past videos, these are likely scenarios

1st amendment audits or 2nd amendment audits can get a little mixed up as I explained, but often times 1st amendment audits become 4th amendment audits. Let’s see how that happens.

From 1st Amendment audit to 4th amendment audit

The officer will demand to search the auditor because they feel that they are “suspicious.” The moment someone searches another individual without their permission or a warrant, or in some cases without probable cause, it is most likely a violation of the fourth amendment and this is how a 1st amendment audit can become a 4th amendment audit.

Here’s a perfect example of a 1st amendment audit that went totally south due to overreaching uneducated (or corrupt) FBI officers.

You’ll notice how the officers never had a reason to detain and search him.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=npxnlhQEtJw

From 1st Amendment audit to 5th amendment audit

These are fairly common and are also known as silent audits. The degree at which each auditor conducts a 5th amendment audits is really a matter of preference.

Some auditors are good at remaining absolutely silent during an interaction with any law enforcement. One specific auditor known for this is “Bunny Boots.“

Other auditors will respond to some interaction simply by stating their rights and asserting that they don’t answer any questions. Another group of auditors engages in normal discourse with law enforcement officers.

But at any time, just like the 1st amendment, any individual can use the 5th amendment and remain silent. It doesn’t matter who is asking, why they’re asking, or whether they plan on making an arrest or detainment.

The only way someone can legally force you to not remain silent is a judge with a subpoena and even then, you can consult with your attorney first.

Here’s a pretty popular auditor that goes by the name The Battousai performing a “silent treatment” 1st Amendment audit.

On a quick side note, The Battousai is the “Turner ” behind the case Turner V. Driver. United States Court of Appeals, Fifth Circuit. — Essentially a case that reinforces the fact that 1st amendment audits are protected by the constitution, especially refusing to identify just “because.”

Sometimes even the 14th amendment comes into play

In some cases we’ve seen, the 14th amendment also comes into play. For example, when an auditor conducting a 1st amendment audit invokes his 5th amendment right to remain silent and the cops arrest him unlawfully or punitively and hold him against his will, they may be denying that person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law. Clearly defined in the 14th amendment.

How does a typical 1st amendment go?

From our perspective as viewers, a first amendment audit often begins with the auditor walking or standing near any one given location. Many times these locations are government related or related to matters of public interest.

First Amendment Audit locations

Some of the most popular places to conduct 1st amendment audits are:

- Police stations

- City halls

- Post offices

- Government agencies (DEA, ATF, FBI, IRS)

- Detention centers, jails, prisons.

- Armed forces reserve stations.

- Military installations.

- Public access events.

- Publicly funded contractors (Aerospace, Energy, Defense, Agriculture.).

- Public utility facilities (electric plants, fuel refineries).

- Airports and transportation hubs.

- Embassies and Consulates.

- Places of worship.

Most auditors make it a point to record these facilities but they make sure they are doing so from a standpoint that is open to the public and legal for them to be in, such as a sidewalk or public right of way.

The most common defense for an auditor is that “the eyes cannot be trespassed” — meaning that if there’s something they can see from a public right of way, then you cannot restrict that view, including the ability to record said view.

In some cases, the audit takes place from other locations that may appear to be off limits but in fact are also open to the public such as the inside lobby of a City Hall, or in the hallways of a building open to the public where the hallways also have unrestricted access, the area surrounding the TSA checkpoints in an Airport and other similar areas.

Most of the time an auditor is free to record an audit from any publicly-accessible point so long as he hasn’t crossed a threshold that puts him or her in a position where they have to agree to posted rules that can be legally enforced and may be different from the common access rules in public areas.

For example, a private property owner may ask anybody to stop recording while standing in or on their property. This includes a liquor store, the front yard of someone’s house, a privately owned museum.

First Amendment audit events

There are also events that are often targeted for first amendment audits, here’s a short list of those:

- Sobriety checkpoints.

- Immigration checkpoints.

- Routine traffic stops.

- Protests and demonstrations.

- Public hearings and public meetings.

- Police interactions with the public.

These type of events can be just as controversial or explosive as the location-based 1st amendment audits because the people representing said event are in a heightened state of mind perhaps because they’re out of their normal element.

A sobriety checkpoint usually is late at night, and it may seem strange for what seems like a “passer-by” to just stop to record the interactions of police with the drivers as they pass the checkpoint.

Many law enforcement departments and units dislike this specifically and have reacted very negatively in the past.

Two auditors that often watch police and checkpoints are Tom Zebra and Katman aka Onus News Service

1st Amendment Audits are judged as “pass” or “fail” depending on the outcome.

Once the location of the audit has been established, and the audit is underway, then it goes on one of two ways.

I’ll describe each one next, one way is that the audit will go remain completely uneventful where the auditor or journalist or photographer is left alone to record and move along as he or she desires and eventually leaves the area with what is known as a “pass” by default for a 1st amendment audit.

I call it a pass by default because there was no interaction. Many times an audit will go without any interaction whatsoever and other times we’ll see the security staff far away on the distance but they don’t do anything or create contact. Both of those are considered a pass.

The other way is with an interaction with a representative from the facility or the event. In some cases, the interaction happens with a regular citizen. These may still end up as having a passing grade, but let’s discuss more first.

1st Amendment Audit pass with no interactions

If an auditor can complete the entire audit without interacting with government officials, police officers, security staff or other types of representative for the facility or event where the audit is being conducted, this is considered a pass.

The videos of these audits are often sparsely filled with commentary about what is being shown on camera or sometimes they have a tangential conversation about the location such as news or recent activity in the area and things of that nature.

1st Amendment audit with contact

Oftentimes when an individual approaches an auditor they refer to this as “contact,” it can be an officer, security guard, facilities manager or just some random staff that works in the building where the audit is being conducted.

These type of audits can go one of two ways, they can be a considered a pass or a fail.

First Amendment audit PASS with interaction.

A pass is when the interaction is cordial, polite and the facility representative or law enforcement doesn’t demand to know why the audit is going on or that the individuals remove themselves or produce a valid ID.

These are often friendly interactions or just plain interactions. A failing “grade” is the opposite.

This video shows a 1st amendment audit pass because the interactions were cordial, non-intrusive and overall friendly.

First Amendment audit FAIL with interaction.

I feel like these are the most watched and the most popular type of interactions shown on Youtube. The first amendment audits that fail often attract lots of comments and more views than the other ones. But there is a good reason, failed audits often highlight corruption, misconduct or violence.

Most of the time, when a first amendment audit fails, is due to a particular breakdown in communications or understanding on the part of the person making contact, usually a law enforcement agent or a facilities manager or representative.

Most of the fails are fails because the person approaching doesn’t know that the auditor is legally allowed to do what their doing. If they’re not willing to confirm that with their superiors, or a manual, or even look at the law or documentation, then it becomes a battle of egos.

If the person initiating contact approaches the auditor with an attitude, the encounter is likely to escalate into a fail. This is because auditors expect to be left alone and they feel they should be treated as any other citizen standing nearby.

Oftentimes we see that the auditors react to the tone and approach that they are confronted with so that if they are approached with a friendly, respectful demeanor they, in turn, react in kind towards the officer or whoever it may be.

But when the opposite is true, you’ll see how the auditors don’t usually hold back giving the person a piece of their mind along with a lecture about the 1st amendment, 4th amendment, 5th amendment or any other related topic.

We’ve seen in some cases where police overstep their bounds and escalate things by detaining, arresting and in some cases even using violence against the auditor simply because they thought they had to enforce a law. Many times it’s just an ego fight between the officer and the auditor and the auditor may face the brunt of it immediately, but ultimately the officer will be held accountable. Or so we hope.

Take a look a this 1st amendment audit fail with an interaction. This one went as far as having the auditor get arrested and illegally detained. But make sure you watch the video after, in the next section. That’s outrageous too!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wATDhcBMIh0

Example of a 1st Amendment Audit Fail

One of the most recent cases of an officer abusing their power against an auditor can be seen in this video by the auditor that goes on by the name of San Joaquin Valley Transparency where a CHP officer baits him into a confrontation and uses force to assert his authority, illegally.

Another example of a fail in 2018 was the one where the chief of police and another high ranking officer attack and take-down an auditor in Morro Bay California.

You can see that next.

Even without violence, many audits fail

A failing grade can also be given when a combination of things take place. You can see that many of these are shown on both of the videos above. Any single one of these doesn’t necessarily constitute a fail in and of itself, but most likely if you see a couple of these pop up throughout the video, then the outcome is likely to be a fail.

- Insisting and demanding the auditor present ID.

- Demanding that they “understand” their security concerns.

- Officer lies or misrepresents the legality of photography in public.

- Officer calls in “in this day and age” argument.

- Officer calls in “danger of terrorism” argument.

- Officer calls the actions of the auditor “suspicious”

- Office calls the auditor’s actions to be disturbing the peace

In some cases you’ll see that an audit turns into a detention or arrest and I believe 100% of the time an auditor or photographer has been arrested, the case has been resolved in their favor. In other words, as a word of caution to police, managers and others that may face auditors in their course of their job.

What is the purpose of a 1st Amendment Audit?

At the very basic level and in the simplest answer what you’re asking is, why conduct 1st amendment audit? Because we can.

And that should really be the end of it. But I’ll give you some purpose in a moment.

People should be able to record and by coincindence or on purpose conduct a 1st amendment audit… because we can, because we are free people and furthermore, the right to conduct a first amendment audit or to photograph or video record in public is protected by the first amendment and has been reinforced by numerous high-level court decisions.

Case Law supporting 1st amendment audits.

We always have to remember that the US constitution doesn’t “grant” us the rights outlined in the 1st amendment. It simply reinforces those rights.

In the same way we should view case law. In many cases, case law doesn’t say that “moving forward” the law has changed, if you pay attention and read the decisions, you’ll find that they are generally worded in a way to show that the right is being upheld and the decision just reinforces said right with either more specific circumstances, or to revoke a previous “ordinance” or similar kind of rule or law.

Phillip Turner v. Lieutenant Driver Officer Grinalds 3825 OFFICER DYESS 2586

This relates to 1st amendment audits, recording the police and qualified immunity. Often cited as “Turner Vs. Driver” and it exists because The Battousai took it to court and won, eventually. Here are more details on it and explains the next couple paragraphs.

Qualified immunity is a thing where a law enforcement agent may claim immunity for doing something wrong but which they thought was right at the time and other reasonable people would also believe it to be right under similar circumstances.

The way I understand it is that if an officer is “keen” on violating one of your rights, but you clearly establish the fact you have that right, and they should not and must not violate it, becase then they know.

They now “know” and their qualified immunity is in jeopardy because they don’t have an excuse to say “I genuinely didn’t know that I wasviolating a basic civil right.”

Clayton vs Colorado Springs PD

I remember seeing this video and I thought the officers involved would be in trouble and it so turned out to be the case. This didn’t go to a supreme court level, but it still matters because the video is textbook how not to handle a person doing public photography.

The case of Clayton vs the Colorado PD turned out that Clayton won $41,000 and I believe they agreed to reinforce the notion that recording in public in and of itself isn’t something to be arrested for or to be considered suspicious.

But it would be incomplete to say that it’s just about the law, instead I have found a few different reasons why someone may conduct a 1st amendment audit. Let’s take a look.

To hold officials accountable

Recording a police stop, or a public hearing or even just every-day activities at one of the many administrative offices that support our local governments should be no big deal. The people working these locations are paid by our tax dollars and they’re most likely in the course of those duties we pay for.

If we are to have transparency of the government and law enforcement it is only right that they can be observed during the course and performance of their duties. Especially when interacting with the public and even more so if they have the authority and power to use deadly force against them.

This is why it is important to record the police when you see them pull someone over. You should record them when you get pulled over. While those may not be 1st amendment audits themselves, the establishment and understanding that anybody has the right to record, apply to all situations.

Are you allowed to record the police?

This video does a good job of explaining in 2 minutes whether people have the right to record the police for example.

There is one thing I disagree with in the video, about how the cops moving you back from a scene to a “safe distance” are just doing it for safety. think based on the videos widely available in Youtube, most of the time when the officer tells them to move back, it is just to push them back so they can’t record or just to interfere with the recording process.

Cops love covering up what they’re doing, all you have to do is watch 1st amendment audit videos in Youtube to find that to be a pretty accurate statement.

To uncover corruption or misconduct.

There are cases where audits have uncovered corruption, or misconduct within a department or an entire police force.

Notably, the Olmos Park story, Leon Valley, Morro Bay and a few other cases are critical to the future of our first amendment rights and the people uncovering these issues are regular citizens, like you and me, “gathering content for a story.”

A more recent incident that maybe even more egregious than any auditor’s video I’ve seen before is the one where the officer drew a gun against a videographer, in plain daylight, literally just because he wanted. Don’t believe me? Here’s the video:

To document a government process

Whether it is a negative point of view or a positive point of view.

The government should work for us and serve us. We are “The People” so it is perfectly understandable to document how the government works, from the local level municipalities to the highest levels.

So whenever possible, many auditors will document things like the process of obtaining a license to carry a gun, the process to file a complaint against an officer, the process of having public records given to us.

Those and many more are perfectly valid reasons to conduct a first amendment audit. While he doesn’t consider it a first amendment audit, ONUS news in California recently documented how the process of obtaining a gun permit worked for him.

I documented part of that video series here Journalist Exposes Broken Process in the Redondo Beach Police Department.

As a time-capsule

Many audits are done with government buildings or city buildings and many of them may be in a landmark area or be landmarks themselves. This is part of our record, this is part of our history. Many auditors record the buildings to document them, to document what is there, why it’s there, what it looks like, what is does the area around it look like, things like that.

Sometimes the locations are really interesting, so this is a totally valid reason.

Many of us get excited when we find footage of what it was in the 1920s. what a particular part of a city looked like back then. Some of these videos may serve that purpose some day. Like this early footage.

For news purposes

Many times recording a police interaction or the ongoings at a public event will result in footage for news reports. In some cases, auditors or journalist will capture important footage just by exercising their right to record.

Many auditors that routinely test the Postal service will use the 2010 DHS memo, or the latest update to it in a 2018 DHS memo as a basis to record a news report. The report comes down to whether this particular facility respects and understands the 1st amendment rights protected by the constitution and whether this facility has been informed of the DHS memo.

Just because

This may seem childish as an answer, but it’s true. 1st amendment audits are allowed and are legal, and you can do them, just because.

At the end of the day, the auditors don’t need to explain themselves to anybody for any reason whatsoever. That’s the core of 1st Amendment audits, the freedom to exercise our freedoms.

As an inhabitant of the USA, they are free to view and record anything they can see from a public place, just because.

Are 1st Amendment Audits Good for something?

As spectators on Youtube, we may feel that auditors are wasting their time, maybe they should get a job, maybe they’re “dumb” or “ridiculous.” — And we would be entitled to that opinion because we have our rights to express that opinion and to believe that opinion.

That entitlement is naturally granted but also protected by the first amendment. In a way, the auditors are exercising a right most of us don’t exercise at all but enjoy daily. If that statement doesn’t make sense to you or you would like me to expand on that, let me know and I’ll explain in a future blog post. But for now, it should be clear by now that 1st amendment audits benefit EVERYBODY.

Ask 1st Amendment Auditors – Video Livestream Q&A

In a 3.5 hour long livestream, five notable auditors take questions from the audience, that’s right over here along with a link to each person invovled. Although it may be long to consume all at once, you can probably break it down into 20 – 30 minute sessions or listen to it as do something else.

Even their “own ” people tell them to knock it off.

In a recent “memo” or just a blog post, the “California Association of Labor Relations Officers” said to law enforcement personnel, in resposnse to the questions “how should we respond to them”? So how should “we” (law enforcement) react to these “audits.”

Meaning how should we respond to 1st amendmnet audits, Sergeant Ryan Brett said the following:

A review of many of the posted audit videos shows us, extremely well trained and professional law enforcement officers acting what I can only describe as “childish” when confronted with an audit and a camera. From us blocking their view, following them, challenging them for ID, or even worse, pulling out our own cell phone and taking pictures and video of them. What is the point? The videos are never taken well by the public audience, and the comments; I won’t even mention them.

I know, some of you may be saying “But terrorists, they scout locations and police stations are a target.” I agree. They certainly do. When was the last time you found a terrorist standing in wide open view, in public, blatantly videotaping a public building with obvious disregard for the police driving around? Probably never. If they were going to scout a location, they would do it and you likely would never know.

That’s just a portion of the memo. I consider that blog post to be mandatory reading for all law enforcement, security personnel and facilities management.

They also suggest educating the party that’s misinformed

On a separate post titled: “First Amendment Audits: Federal Buildings” they say:

Just like all other actions with photographers, respond with regards to the Constitutionally protected rights in mind. I implore you to weigh the totality of the circumstances and only take enforcement action (based on reasonable suspicion or probable cause) when it exists unequivocally and obviously. The best response lies with you contacting the reporting party (usually the federal security or employees) and informing them of the laws. You will save them and yourselves a lot of work.

In order to be better informed, please take the time to review the de-classified DHS Memo dated 08/02/2010 regarding photographing of Federal buildings. Also of significant importance, is the case law established in Fordyce v. Seattle regarding photographing public officials in the course of their duties. The bottom line is simple: it is NOT illegal to photograph the exterior of these locations. Level headed thinking and knowledge before you go is still the best approach to these types of contacts.

Another quick read that should be mandatory for everybody. Essentially, the responding officer should inform the complaining party that the DHS 2010 memo exists and that the photographers are well within their rights.

But you’ll see that many times the officers do NOT educate the party that complained, and sometimes they even take punitive action towards the videographers.

Counter points to 1st Amendment Audits and Auditors

It’s hard to say “cops” this or “postal employees” this, but for the sake of argument, just to explain it below, I’m going to refer to people that approach the auditors as “contacts” as in the people that make contact. I don’t want to classify all encounters as being with cops or all encounters are with postal employees for example.

Although I have to say as a side note, the majority of the times the contacting party is an actual police officer.

But here’s a list of situations that 1st Amendment Auditors face regularly which can be considered the main counterpoints people have in favor of interrupting a 1st amendment audit in order to demand identification, detain, interrogate or arrest someone.

Contact says they have security concerns.

This one is so basic, watch any of News Now Dallas, or High Desert Community Watch, Jeff Gray, News Now Houston, or 1/2 of the other auditors and you’ll find this in most of their videos.

The contact will use quotes along the lines of these:

- We have security concerns with you recording our facility.

- That’s a secure area over there and you’re not allowed to record it.

- We don’t allow recording of our security check-points.

Sounds like a reasonable bunch of reasons. The problem is that those are just feelings and policies. Internal policies. Oftentimes, the contact person will point to a sign that says “no cameras.” And deliberately overlooking that the sign is meant as a sign to indicate “beyond this point.”

And that is just a policy anway. Not law. As mentioned elsewhere in this page, there is nothing that is visible from a publicly accessible vantage point that can be restricted from being recorded.

If a security checkpoint is so sensitive that it should not be recorded then it should be behind closed doors in a restricted area.

As HDCW says from time to time, your security concerns don’t trump my rights.

Contact says they’re in a restricted property and must leave.

This happens in many cases. Security or law enforcement and it happens a lot with Postal 1st amendment audits; the postal employees will often say that the auditor is in private property.

The contact claims that they are not allowed to be on the property and or cannot record while on the property, in areas like the outside grounds, or like the lobby or publicly accessible areas at a post office.

Sounds reasonable too, right? You would be correct.

This is totally reasonable, to ask someone to leave somewhere they’re not supposed to be, after all if it’s private property we’re talking about then the auditor should not be on it if no permission was given or is implied or in the case where it was given, it now has been revoked.

The problem is that many times the contact will claim the auditor is in private property when they are not. Postal property where is not restricted to employees or postal personnel only is accessible to the public is considered “public.”

The area could be private if you didn’t analyze it.

Most auditors come prepared to their 1st amendment audits and know exactly where the property lines are, what parts are part of the common public access areas and stuff like that.

The problem is that many times the contact will claim the auditor is in private property when they are not. They think they own up to the edge of the road.

Most times this is wrong

Often times security personnel and facilities managers will be under the impression that their property goes all the way up to the edge of the street for example. This leads them down the false belief that they are in charge of the sidewalk, or in the absence of a sidewalk in charge of the public right of way.

Most places, if not all places in the US have right of way designations along streets and highways where the public is allowed to access. This is the area where you would pull over if a shoulder is absent on the road, or where you would walk if a sidewalk is missing. It’s also generally where the city or count will run wiring and plumbing for public utilities as well as where the public information signage is placed. Things like speed limit signs, road name signs, go in publicly accessible land.

This is often mistaken for private property so before you think that a crazy postal worker or security guard was right to claim the auditor was trespassing, make sure that is accurate.

Contact says they’re in a restricted property and can’t record

This sounds similar to the previous case but it’s slightly different. This often comes up when the auditor is inside a building. It can be a city hall, library, or other publicly accessible buildings.

Oftentimes a marshall, or a city clerk, or security guard will tell the auditor that they’re inside of a building which restricts their right to film.

Sounds reasonable right? I mean, it’s just like in a museum or a store right? If they ask you to put the camera away, they have the right to tell you that. Don’t they?

Most people think that you can’t record in public and if an “official” person tells you to stop, you should.

The places where videography is really restricted will have a sign posted that indicates so. Many of these are under debate now in various court cases and we’ve seen results with audits go all over the spectrum when recording in some of these “restricted” areas.

Most notably and most agreed upon location where it is okay to restrict recording is inside a specific courtroom because a specific judge has banned cameras. But even this notion is being questioned in some cases.

The conclusion to this point is that private property definitely can dictate the rules for photography or videography, but most public property is fair game for 1st amendment audits.

Contact says you can’t record their face without their consent.

This happens a lot in busy public spaces where a 1st amendment audit is being conducted. For example an airport, or a public demonstration.

It is a common misconception that people must consent for you to record them. This is clearly false, as if it were true, the paparazzi would not have a job.

The truth is that just like I said before, you can record anything you can see from public. That includes recording people even private individuals.

The misconception that anybody has to give consent to be recorded first comes from the notion that you can’t use someone’s face to make money without their consent.

This means they assume that the video will be used for profit. First Amendment audits are considered news and public press and not a for-profit endeavor so no permit or license is needed to shoot the video nor to include the people that were transient in the video.

The most ironic situation that falls under this section is when the contact approaches the auditor and demands not to be in the video. The irony if you don’t get it is that they are coming up to a camera that they know is recording and they stand in front of it then demand not to be in recorded…

Contact says you can’t loiter in public areas.

Sounds like a cop could use this to send you moving along so you wouldn’t be able to record them or record something.

Sounds normal doesn’t? Most people think that if a cop tells you to “move along” you should. But you don’t have to if you’re in public and you’re allowed to be there. That’s it!

Officers will often say that if they’re just standing there, they’re loitering and sometimes they threaten the auditor with detention or arrest saying they can’t loiter. But you can’t really loiter in a public space, I could be mistaken, but I thought loitering rules were for private property that is accessed by the public, like the foyer in a shopping mall.

The other counterpoint to the loitering accusation is that loitering stipulates that you’re not doing anything with a purpose. But the very act of recording on a video recorder is purposeful so loitering doesn’t even apply.

Officer says they got called and they are just responding

This one is strictly for officers because they’re the only ones that have the authority to do this, or they think they do. This one is usually a fail and ends up being a negative interaction because the cops simply blame someone else for them being called out.

Officers will say stuff like “we are just responding to a call we got on you” OR “we are just responding so we have to document your name and DOB” —

Well the problem is that cops can’t hide behind that excuse when it comes to civil rights. Just because a neighbor called to complain, or a store manager called to complain or a postmaster, doesn’t mean their complaint has any legitimacy. Besides the question of legitimacy about the complaint, the officer is there to investigate the facts of the complaint.

The proper response to complaints against public photography is to let the caller know that if they are not doing anything else that constitutes a crime, video recording or photographing in public is not a crime, it doesn’t matter which way the cameras are pointing.

The police officer that has to respond to the scene should first and possibly only address the party complaining and let them know what the auditor is doing is perfectly legal, as annoying as it may be.

In Conclusion

What’s a first amendment audit? – It’s when someone video records a publicly-accessible area or event protected under the umbrella of the 1st amendment’s freedom of press and freedom to assemble with others and freedom of speech.

Generally, the “auditors” research their audit in advance and will generally be correct in their assertion that they’re legally allowed to do what they’re doing. Even CALRO says in one of their blog posts to know that the auditors are well prepared, and generally the responses from law enforcement has been poor in the past.

1st Amendment audits may be annoying or seem “dumb” but they’re just little ways to excercicese our 1st amendment rights. As evidenced in the videos, many people still don’t know we have such rights and will often try to step over these rights in the name of “security” or “officer saftety” or for the sake of other people’s “feelings” because they feel “uncomfortable.”

1st amendment audits are also in question sometimes when people think they must give explicit consent to be in video when in fact they have no expectation of privacy when they’re in public so they can be videographed or photographed without their consent.